Post-Mortem

December 8, 2018

Last week, I flew down to Texas to attend my grandmother’s funeral. I took the opportunity to not only reconnect with family, but to see firsthand many of the places that figure prominently in my history and imagination. Just as writing my grandmother’s obituary has helped, in some small way, to find a purpose in her passing, inhabiting the transformed landscape of my youth for a few days has helped me to understand my place in a larger story.

My flight landed at Love Field on an unseasonably warm afternoon, and I drove a rental car through the sprawling Dallas/Fort Worth Metroplex to Southlake, one of the many suburbs of Dallas. I lived in

Their house sits on newly-developed ranchland that still sees the occassional roadrunner (now darting along bone-white sidewalks), or even a cautious bobcat. Grand, comfortable McMansions line deserted streets with vaguely Anglo-Saxon names. The quiet, the big, blue Texas sky, and the mass-produced homes seemed at once alien and familiar. The night sky appeared surprisngly dark considering the number of Christmas lights in the neighborhood.

The next day I drove out to Weatherford, first to the funeral home to view Grandma in her casket, then to the little house where she lived her final days, and where I could visit with relatives, see her surroundings, and prepare for the upcoming service. I had never seen this place, but it looked much like any other small suburban home, with tall, wooden fences, hushed streets, and the occassional barking dog.

The backyard faced out onto open prairie, and I thought of her sitting on the porch in the morning, waking up with the birds and grasshoppers. Tall, flaxen grass sighed with the passing breeze, and I saw a distant buzzard wheeling in the sky like a black kite.

After the funeral, my sister and I visited the old house in Aledo, where my grandparents lived for many years. As a child I felt at home in this place — the old stone house, the sagging barn, surrounded by a sea of pastures and wild grassland — but now the house sat uninhabited, bereft of life, like a corpse. I felt only a superficial connection to this once-familiar place, just as I felt only a superficial connection to the body in the casket earlier that day.

Wandering the grounds, I encountered a 3-foot long snakeskin, dry and brittle but fully intact. I took it, thankful for the good omen.

In the land behind the house, just behind the trees and brush, one could faintly glimpse a flurry of activity as heavy machinery dug out lots for the new housing development, filling the air with the sound of gunning engines and metal scraping against rock, like a knife scalping the earth. The Walsh Ranch had once owned all this land, but they sold out to developers, and I don’t know what will happen to the old house — it may become a real estate office, or the developers may tear it down.

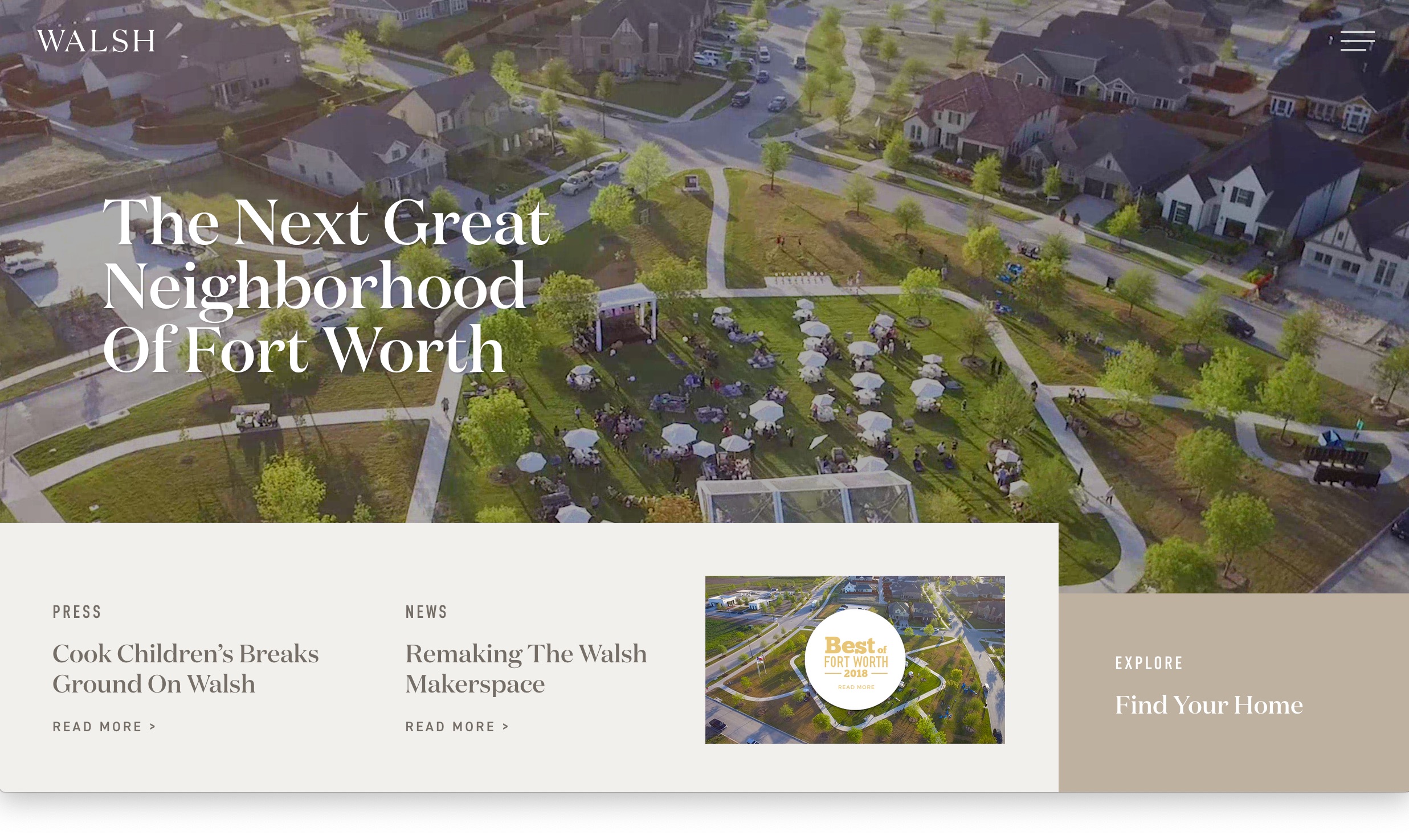

My sister and I explored this strange new landscape. I later learned the name of the development — Walsh Village — and looked up its website. The marketing material made it look like a place where one could belong, a good place to raise a family and find community, but a place completely isolated, a place without a place, like a scale model sitting on a table.

We drove through the winding streets of Walsh Village in the light of a dusty, dystopian sunset, passing houses in various stages of construction, some with occupants, their grassy lawns dotted with plastic candy canes and inflatable snowmen. Yellow machines toiled in the denuded Martian landscape surrounding the Village. I felt oddly okay with this. My time here had passed long ago, and I came now as a visitor, a witness to ordinary and predictable human destruction. Someday these houses would fall back to dust, reduced to a few shards of toilet porcelain, a thick, rusty sewage pipe, a Caucasian doll’s head, all of it hidden in tall switch grass, with nobody around to mow it.

After all, in the late 1970’s, during my kindergarten year, I had moved with my family to a similar newly-built subdivision near Dallas, called The Colony. I remember exploring the vacant, stick-frame houses, playing on concrete slabs, wandering the same quiet, winding streets, under the same big sky. Some years ago I wrote a poem about it:

New Suburb Most of the houses Were empty; they’d just Finished building. And No lawns, just red dust And stickers, and clouds So fast and high and Clean you could actu- Ally wash your hands In them. There were vac- Ant lots and vacant Winds, that death-quiet Left from some absent Nature who gave green Growing things to luck- Ier folks and left Us alone to buck- Le down in Texas. Hot sidewalks, always The sound of a free- Way somewhere, and days Stretched to the hori- Zon - vast, beautiful Days. Later there’d be Ghosts (whole houses full) And tall fences with Weeds and dogs running Alongside them, and He’d catch me hiding In a makeshift fort, Made of plywood boards, With a carpet door- Way opening towards The soggy morning sun.

The next morning I headed to Grapevine to “take a walk by the old school.”

Dove Elementary looked largely unchanged from my memory of it. The big field where I had once played lay untouched — even the soccer goals remained. The interior seemed well-preserved and friendly when I peeked through a window.

The vacant land across from the school had become apartments and condominiums sometime in the 1990’s, and another wall of apartments, built during my time there in the early 1980’s, lined the back of the soccer field. Each phase of growth had a distinct architectural style, exaggerated by the monoculture of design patterns employed for each cluster of buildings.

I walked down Sagebrush Trail to my old house, built in the 1970’s. The current occupant stood bent over on the roof, stapling a line of Christmas lights to the eaves. I chose not to introduce myself, instead snapping a picture with him safely obscured behind a tree.

I walked through the old neighborhood. How little it had changed — trees had grown, cars looked different, but the little ticky-tacky houses and yards had the same character that I remembered.

I discerned a distinct personality in each house I passed. Like seeing the faces of old friends.

But more than nostalgia, I felt a sort of detached interest. The houses had a plain, retro charm — low, flat, composed of a handful of geometric forms combined in a slightly different way for each iteration.

I once rode a Huffy bike on these streets. I knew where each street led, I knew where my friends lived. I knew which yard to cut across to reach the forest, with its dirt trails leading eventually to the shores of Lake Grapevine. Now I had only a faint intuition of where to go, but I didn’t care.

I saw no human beings, other than the man putting lights on my old roof. No children played in the streets. No cars passed. I wandered like a tourist in a place nobody ever visits.

Eventually I left the old neighborhood and drove out to Grapevine Lake with a thought to drive over the dam, but when I got to the dam, a sign blocked the way. So I got out of the car and walked.

The dam had always intimidated me as a child, but now, a grown man standing alone on top of it, I felt untouchable. Everything about the dam seemed beautiful — the details of the asphalt, the leaning of the utility poles, the waves splashing against the jagged rocks below, the long, clean line separating water and land.

A strong wind blew over the top of the dam from the lake, and I found myself drawn to a mysterious clanging sound. I found the source — a loose metal “1” nailed to one of the utility poles: number 13. My lucky number — another good sign.

And I realized that my 8-year-old self, upon finding a deserted stretch of road on top of this dam, would probably do just as I found myself doing now — walking with hyper-awareness, enjoying the solitude and the strange beauty of the place, feeling a strong connection to the details provided by chance. And so I became aware of a kind of wholeness, a continuity in myself across the years. I have not changed so much after all.

Maybe this dam and artificial lake it creates will endure after generations of people and their houses have come and gone. Or maybe one day the iron gates of the spillway will break, the water rushing to the other side, the lake emptying out to uncover once-sunken fishing lures and beer cans. I thought these things as an airliner, taking off from Dallas/Fort Worth Airport, flew overhead, glinting in the sun, silvery as a fish, seemingly close enough to touch. The next day, I boarded my own flight, and returned home.